- General Assembly leaders plan to redraw state legislative districts, but their plan might not comply with the North Carolina Constitution

- The North Carolina Supreme Court has reopened the redistricting process with a recent ruling in Harper v. Hall

- The renewed redistricting process would likely result in the overturning of Harper v. Hall by a new Supreme Court majority next year

The recent North Carolina Supreme Court ruling on redistricting could pave the way for the General Assembly to draw new state House and Senate districts in 2023, sparing legislative leaders from taking a more constitutionally suspect path toward that end. It could even result in the court reinstating the legislative maps it struck down about a year ago.

General Assembly Leaders Plan to Redraw Legislative Districts

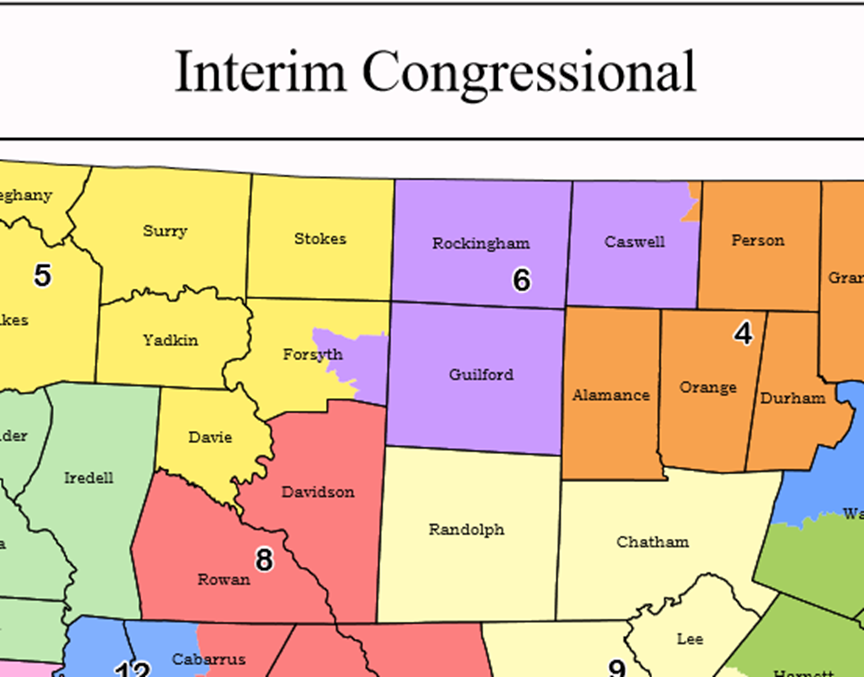

Everyone involved in the redistricting process acknowledges that the General Assembly has the authority to redraw congressional districts to replace those drawn in early 2022 by a panel of court-appointed special masters. The General Assembly even officially refers to it as the “Interim Congressional” map.

Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger and House Speaker Tim Moore also plan to redraw remedial state legislative maps the General Assembly drew under court order, although there is a problem with that idea:

Berger said he “suspects we’ll look at” redrawing legislative districts again, too, although the state constitution forbids lawmakers from redrawing maps without court action after they’ve drawn them once per decade.

Article II, Sections 3 and 5 of the North Carolina Constitution state that, once “established,” state House and Senate districts “shall remain unaltered until the return of another decennial census of population taken by order of Congress.” The next census is not until 2030.

Legislators could argue that the current maps were drawn outside the constitutionally specified process and thus not “established” since they were done under court order. That would absolve them of the once-every-ten-years limit on drawing maps. However, such a theory is a stretch since the General Assembly, and not the courts, drew the current maps.

Now, the outgoing Democratic majority on the North Carolina Supreme Court may have just given General Assembly leaders a clear constitutional path to replace the court-ordered legislative maps.

North Carolina Supreme Court Forces Yet Another Redraw

The court handed down two election-related rulings on Friday, December 16. Both were 4-3 party-line decisions.

They included a second ruling in Harper v. Hall, the case that overturned both state legislative and congressional districts, resulting in remedial legislative districts and court-drawn congressional districts. The high court upheld the trial court’s acceptance of the state House remedial map and rejection of the remedial congressional map. It overturned the trial court’s approval of the Senate remedial map, however.

The court invoked General Statute 120-2.4(a1) in its order remanding the case back to the trial court. That statute allows the court to “impose an interim districting plan for use in the next general election only.” The order further directs the trial court to “oversee the creation” of a new Senate map by modifying the Senate remedial map “only to the extent necessary” to achieve what the court calls “constitutional compliance” (page 52 of the opinion).

It is worth noting that the order skips 120-2.4(a), which gives the General Assembly the first chance at drawing remedial maps and goes straight to 120-2.4(a1), which directs courts to draw interim maps.

Armed with that order, the trial court will likely bring back special masters, who analyzed the legislative maps and redrew the congressional map last February, to draw an interim Senate map for the 2024 election.

Lame-Duck Court Gives the General Assembly a Path to Redraw Legislative Maps

So, how would this legal setback lead to an eventual victory for General Assembly leaders?

Once the trial court approves a new Senate map, Berger and Moore will immediately appeal. That will eventually bring the case back to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court could even speed up the process, citing the same “great public interest” the court used earlier this year to bypass the standard procedure for appeals in the case.

If there is doubt about how the Supreme Court’s new 5-2 Republican majority will rule, a reading of Chief Justice Paul Newby’s dissent in the court’s first ruling in Harper v. Hall will overcome it. He wrote that the ruling “violates separation of powers” (page 10), “tosses judicial restraint aside” (page 13), and was “judicially amending the constitution” (page 17). Supported by a new majority, Newby will chart a new course limiting the courts’ power to adjudicate partisan gerrymandering claims.

In short, the “Harper standard” (the redistricting criteria the North Carolina Supreme Court laid out in its first Harper v. Hall ruling) is a dead man walking.

With the death of the Harper standard accomplished, the court would have two options. The first would be to order the General Assembly to redraw both House and Senate maps considering the new ruling. The second would be to restore the status quo ante by ordering the General Assembly to use the legislative maps the General Assembly originally passed for the rest of the decade.

How Did It Come to This?

The outgoing North Carolina Supreme Court majority showed an inclination towards political calculations throughout the Harper v. Hall process. That is evidenced in the vague standards they imposed to allow them to reject any maps they deemed insufficiently helpful to Democrats and in their manipulation of the judicial schedule. So, it is unclear why they did not see how this second ruling would directly lead to a reversal in the inevitable third ruling sometime in 2023.

In any case, that third ruling in Harper v. Hall, not the first or the second, will set a precedent for how North Carolina courts handle redistricting claims in the future.