A court filing has revealed serious allegations of vote buying in a county commissioner race in the March 5 primary. While shocking, vote buying is hardly new in North Carolina.

Allegations of Buying Votes in Robeson County

Lacy Cummings, who lost to Sampson in the March 5 Democratic primary 875 to 870, filed the court petition only after both the Robeson County and North Carolina State Boards of Elections denied Cummings’ protest of the result:

Commissioner Wixie Stephens allegedly paid at least nine residents up to $60 to vote for incumbent Judy Sampson in the March 5 Democratic primary for the commissioners’ District 5 seat, according to a legal petition filed on Thursday in Wake County Superior Court.

Lacy Cummings, who lost to Sampson in the March 5 Democratic primary 875 to 870, filed the court petition only after both the Robeson County and North Carolina State Boards of Elections denied Cummings’ protest of the result.

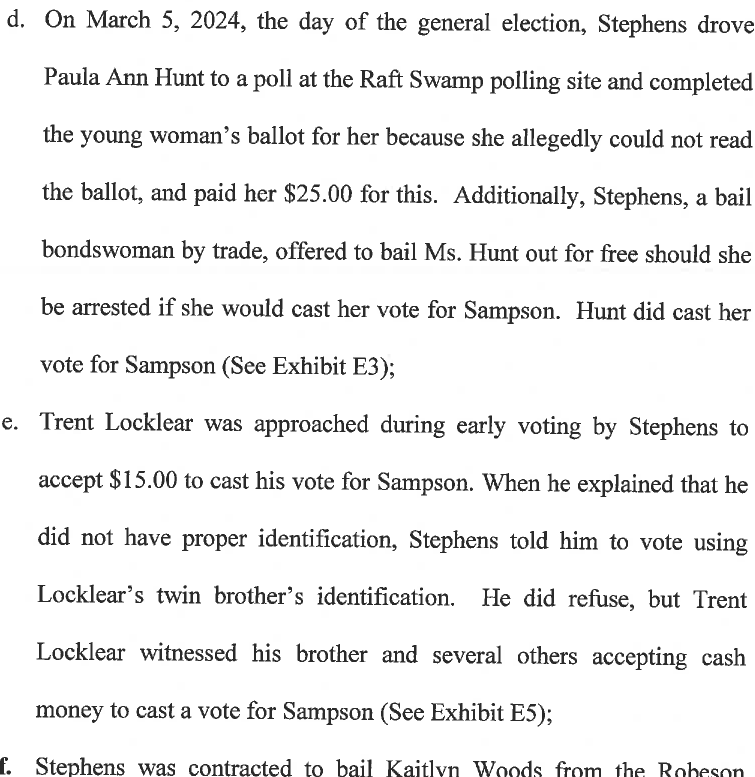

As seen in a detail from the filing below, Cummings has witness statements detailing serious incidents of election fraud:

The filing is the start of what may be a long legal process; prosecutions related to McCrae Dowless’ alleged ballot harvesting in the 2018 9th Congressional District race were not resolved until 2022.

The procedural side of the complaint will proceed more quickly since deciding who the Democratic nominee is will have to be done before general election ballots are printed in late summer. A judge has temporarily blocked certifying the primary in that race.

A Long History of Vote Buying in North Carolina

Under North Carolina law, it is a felony “for any person to give or promise or request or accept at any time, before or after any such primary or election, any money, property or other thing of value whatsoever in return for the vote of any elector” (163‑275.(2)).

That has not stopped people from buying votes in North Carolina. In one example, five people were convicted in 2004 of vote buying in Caldwell County.

A local newspaper found evidence of systematic election fraud in the 2010 Yancey County Sheriffs race, including an offer for reduced criminal charges in exchange for voting:

Soon after the details of the illegal votes were documented in the newspaper, one of the felons who illegally voted came to the offices of the Yancey County News to complain about the story. When it was pointed out to him that the report was true and accurate, he told to a newspaper employee that he had voted illegally because then-chief deputy Tom Farmer had approached him and offered to reduce charges that had been filed against him in return for his vote.

Noone was ever convicted for what went on in that race.

Nor is vote buying in North Carolina just a recent phenomenon. Perhaps the most shocking revelations of vote buying surrounded Project Westvote, a federal investigation into systemic election fraud in western North Carolina in the 1980s (pages 21-22). The investigation resulted in dozens of convictions across several counties.

As with many crimes, those caught and convicted for voting buying and other election crimes represent just a fraction of the total crimes committed.

One reason that the conviction rate for election crimes is low is that it is difficult to prosecute. There is little doubt that the witnesses who said they saw or experienced those crimes will face pressure to change their statements before trial, assuming there is a trial. That is especially true since witnesses often have to testify against friends and relatives. Even if they stick to their statements, a lack of physical evidence (vote buying produces little to none) will make any trial boil down to a case of “he said, she said.” Such cases are hard to prosecute.

While election crimes should be thoroughly investigated and prosecuted, we must also strictly enforce election integrity measures, such as same-day voter registration verification and the two-witness requirement for mail ballots, to help minimize the impact of those crimes.