A new political party may be on North Carolinians’ ballots in 2024. But the Democratic Party-controlled North Carolina State Board of Elections (SBE) has delayed approving their petition. It fits a national pattern of Democrats seeking to deny voters that choice on their 2024 ballot.

What is “No Labels”

No Labels is a centrist organization that seeks bipartisan consensus across issues. It helped start the Problem Solvers Caucus, a bipartisan caucus in the US House of Representatives. The caucus includes three North Carolina members, Democrats Don Davis and Wiley Nickel and Republican Chuck Edwards.

The national No Labels organization also has a North Carolina connection. One of their cochairs is former North Carolina governor Pat McCrory. The other is former NAACP head and North Carolina-based civil rights leader Ben Chavis. Chavis explained his motivation for working with the group in an interview with the Carolinian:

I feel that No Labels is the fulfillment of Dr. King’s concept of the ‘beloved community’ where we work together in a bi-partisan way; Black and White, Native American, Asian-American and Latino. Americans should be working together. The more I work with Gov. McCrory, the more we dialogue together, the more we have civility together, the more we discover our common interests.

McCrory added, “We’re fighting the status quo. We’re breaking from the labels both of our parties have given us.”

The group recently pitched itself to Republican donors as an “anti-Trump alternative.”

No Labels Party Gets the “Green Party Treatment” in North Carolina

Before No Labels can put their candidate for president on the ballot in North Carolina, they must become an official party in the state.

Under North Carolina law (GS § 163-96.), there are two objective criteria for party recognition petitions:

- The petition must have signatures from registered voters equal to 0.25% of “the total number of voters who voted in the most recent general election for Governor.” At least two hundred must be “from each of three congressional districts.”

- Each page of the petition must have a header listing the name of the proposed party, that the petition is for the formation of that party, and the name and phone number of the proposed party’s state chairman.

Election officials have verified 14,837 petition signatures from No Labels, more than the 13,865 they need. They meet the three-district portion of that criterion as well. Also, the SBE has not indicated anything improper about their petition forms.

With both objective criteria for state recognition met, SBE Chairman Alan Hirsch shifted focus to a subjective measure. He refused to bring the petition up for a vote at the board’s July 27 meeting (starting at the 46:20 point). His stated reason was that No Labels needed to do more to prove that it satisfied another provision of the statute: “the organizers and petition circulators shall inform the signers of the general purpose and intent of the new party.”

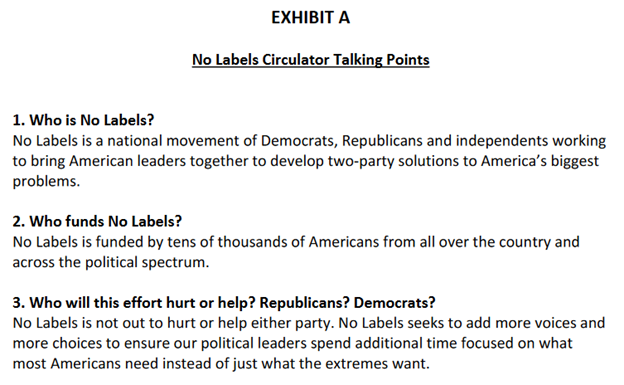

In response to a request from Hirsch, No Labels’ Director of Ballot Access, Nicholas Connors, submitted an affidavit to the board stating that the group “provided information to its petition-circulators about No Labels’ purpose and intent” and “instructed those petition-circulators to communicate this information to potential petition-signers.” The affidavit also included an example of talking points they provided their petition gatherers stating their general purpose (see figure below). That was not good enough for Hirsch, who said he was concerned that it was “not sufficient.”

Hirsch gave no indication of what a “sufficient” description would look like, and no other board members, from either party, spoke on the matter before he tabled it.

No Labels saw the move as a partisan action:

Make no mistake, this delay is not simply a case of bureaucracy gone awry – it’s partisan activists protecting entrenched party interests through any kind of underhanded way they can, using rope-a-dope tactics to drag out our effort and keep us off the ballot in 2024.

If you think you have seen this play before, it is because you have. The SBE similarly sought to prevent the Green Party from getting on the ballot ahead of the 2022 election. It took public pressure and a lawsuit to get the SBE to do its job:

The Green Party also faced endless bureaucratic red-tape and legal hurdles that went right up to, and even beyond, the deadlines. In the end, after great pressure, the state board of elections approved the Green Party to run candidates, and a federal judge ruled that because they had met all the actual legal requirements and the delay wasn’t due to their own negligence, they would have to be allowed on the ballot.

Figure: Exhibit provided by No Labels to the State Board of Elections before the board’s July 27 meeting (Source: North Carolina State Board of Elections).

The National Context of the State Election Board’s Actions Against No Labels

Hirsch’s action makes more sense if put in the context of organized nationwide efforts to keep No Labels off the ballot, an effort they believe will hurt President Joe Biden’s chance of winning in 2024:

Top Democratic strategists, including current advisers to President Biden and former U.S. senators, met last week with former Republicans who oppose Donald Trump at the offices of a downtown D.C. think tank.

Their mission: to figure out how to best subvert a potential third-party presidential bid by the group No Labels, an effort they all agreed risked undermining Biden’s reelection campaign and reelecting former president Donald Trump to the White House.

Whether No Labels is a real threat to Biden’s reelection does not really matter to those trying to stop them. What matters is the perception that the group is a threat to Biden. That perception is fueling Democrats’ efforts to keep it off the ballot.

Toward that end, Democrats in Arizona have sued the state to get No Labels off the ballot. In Maine, Democratic Secretary of State Shenna Bellows accused the group of misleading voters, a possible precursor to denying them ballot access.

In North Carolina, Hir grounds for dismissing No Label’s petition despite their meeting the objective legal criteria for recognition. Even if they succeed in being officially recognized as a party in North Carolina, the time and money spent in the effort drain resources they could otherwise use to gain ballot access in other states.

This raises a question: Would SBE Chair Alan Hirsch’s action against No Labels be any different if he were just a partisan hack trying to please his party bosses? It is hard to see that there would be any difference at all.

The SBE caved and added the Green Party to the 2022 ballot after public pressure and lawsuits. It may take a similar effort, or at least the threat of one, to get No Labels on the ballot in North Carolina for 2024.