Redistricting lawsuits are common in North Carolina. The General Assembly’s redistricting page is littered with maps that courts have tossed out (click on “District Plans Enacted or Ordered by the Court”).

Only One Redistricting Lawsuit so Far

However, unlike in the recent past, there has been no rush of lawsuits against the new maps. Only one lawsuit has been filed so far, and that complaint only seeks to directly change two districts in the northeastern part of the state (although it could result in a cascade of changes to many other districts). Even in that suit, lawyers waited 26 days to file their complaint (Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections).

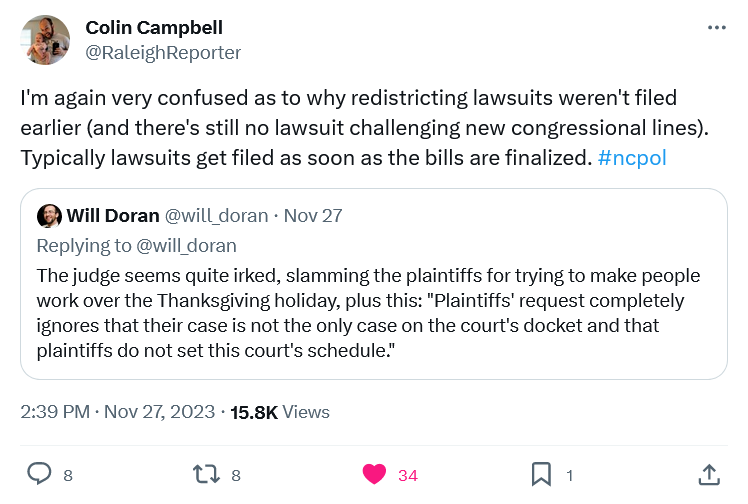

The lack of lawsuits has left the state’s political observers scratching their heads:

Closed Paths and Weak Cases

There are a couple of reasons for the dearth of redistricting lawsuits. First, there is no path for successfully arguing claims of partisan gerrymandering. The United States Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019) that “partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts” (page 30). The North Carolina Supreme Court came to a similar conclusion in Harper v. Hall (2023) that “claims of partisan gerrymandering present nonjusticiable, political questions.”

To be sure, legislators cannot simply draw any districts they want. They must comply with the North Carolina Constitution, the United States Constitution, the federal Voting Rights Act, and related court rulings. As stated by Stephenson v. Bartlett (2002), the state constitution limits partisan gerrymandering by requiring the General Assembly to keep counties whole to the maximum extent possible.

The other common avenue for redistricting lawsuits is based on claims of racial gerrymandering in violation of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) or the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

However, there are no obvious avenues of attack on that front either. Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections focuses on state senate districts in the so-called “Black Belt” region of majority-black counties in northeastern North Carolina. That area comes the closest to meeting the “Gingles test” of criteria plaintiffs must meet to prove racial gerrymandering claims under the VRA.

While we will provide a fuller analysis of Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections later, a look at the complaint reveals that both of the plaintiff’s proposed remedial maps use race as the predominant factor in drawing districts, which violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Cooper v. Harris, 2017).

Forecast: Clear Skies for Candidate Filing

US District Judge James Dever rejected the Pierce v. NC State Board of Elections plaintiffs’ request for an expedited preliminary injunction in harsh terms:

“Plaintiffs do not explain why they waited 26 days to file this action and 28 days to move for a pre1iminary injunction,” he wrote. “In so waiting, plaintiffs belie their ‘claim that there is an urgent need for speedy action to protect [their] rights’ or that their entitlement to a preliminary injunction is clear.”

“Moreover, plaintiffs fail to justify giving defendants one business day to respond to plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction, which plaintiffs waited to file until the day before Thanksgiving,” Dever added. “Thus, plaintiffs ask the court to expedite defendants’ response to a motion before the court or defendants know the contents of that motion…”

“In sum, the court DENIES as meritless plaintiffs’ emergency motion to expedite,” Dever concluded.

That injunction would have stopped candidate filing for the 2024 election, which runs from December 4 to 15. With Dever’s shooting down of the preliminary injunction request, filing is unlikely to be interrupted.