- The first sign that something was amiss in the 2010 Yancey County sheriff’s race was an anomaly in absentee-by-mail ballots

- Eye-witness accounts detailed allegations of absentee ballot fraud, voter registration fraud, and illegal voting by felons

- Despite credible evidence of fraud, a new election was not ordered, and nobody was prosecuted

Although election fraud can take various forms, voting by mail (known as absentee voting in North Carolina) is uniquely vulnerable to fraud. When law enforcement and election officials fail to act against suspected cases of fraud, our elections are less secure, and voters’ trust that the results accurately reflect their will diminishes. Such was the case in the 2010 race for sheriff in Yancey County, North Carolina.

An anomaly in Yancey County

The first noticeable thing about the absentee ballot vote in Yancey County in 2010 was how disproportionately large it was.

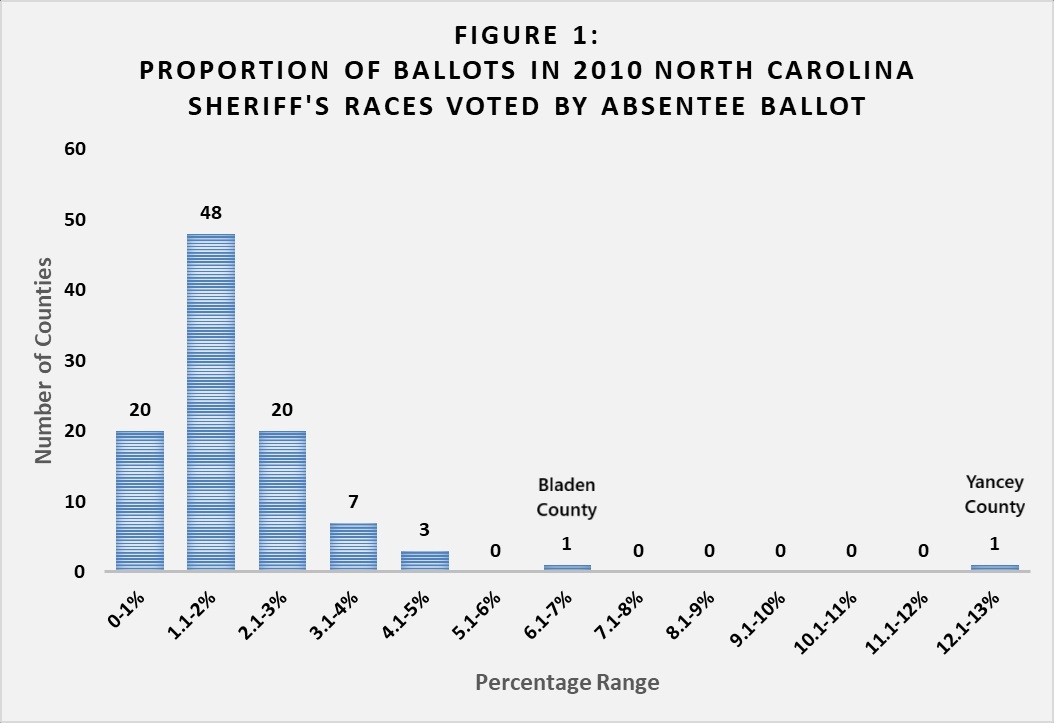

Comparing the absentee votes for sheriff in Yancey County to those in North Carolina’s other 99 counties reveals an anomaly. The proportion of votes cast through absentee ballots in Yancey County was 12.6 percent. That is more than six times the 1.9 percent average for the other 99 counties. As seen in Figure 1, Yancey County was an extreme outlier.

The only other county with more than five percent of all votes for sheriff coming by way of absentee ballots was Bladen County with 6.2 percent. McCrae Dowless, who was later at the center of a ballot-harvesting controversy that led to the overturning of a 2018 congressional election, worked for several campaigns there in 2010. It is worth remembering that the “disproportionately high level of absentee ballot usage” that initially triggered concerns in the 2018 Ninth District congressional race was 7.3 percent in the portion of the district located in Bladen County.

As seen in Figure 2, Gary Banks, the incumbent Republican candidate for sheriff in Yancey County, received a higher proportion of votes by absentee ballot (14.6 percent) than any other candidate for sheriff in North Carolina in 2010. The second-highest proportion was 10.4 percent for Jeff Neill, Banks’ Democratic challenger.

The candidate with the third-largest proportion of votes cast by absentee ballot was Prentis Benston, in Bladen County, at 7.5 percent. As noted in the book “The Vote Collectors,” Benston was heavily backed by the Bladen County Improvement Association PAC, an organization whose “get-out-the-vote” workers had, according to eyewitness accounts, illegally collected ballots.

Why focus on races for sheriff? Eyewitness accounts suggest that Yancey County’s unusually high proportion of absentee ballots was due to activities related to that contest.

Eye-witness accounts of election fraud in Yancey County

Sheriff Gary Banks’ family had been a force in Yancey County politics long before the 2010 election. His grandfather, Donald, and his father, Kermit, had held the sheriff’s office at various times since the Great Depression.

Banks found himself in a closely fought election that year, however. It was his first campaign after being appointed sheriff upon his father’s retirement.

What happened next may have been lost to history were it not for the existence of Yancey County News. The paper investigated several allegations of election fraud surrounding the sheriff’s campaign. The paper and its webpage have since been shuttered, but links to some articles are available through the Wayback Machine online service. Some of the allegations the newspaper uncovered include:

- Sheriff’s Department Captain Judy Ledford delivered absentee ballots to voters and took possession of them after the voters completed them (a felony under North Carolina law). Sheriff Banks later claimed that the voters’ “memory is incorrect” about Ledford taking their ballots.

- Chief Deputy Tom Farmer approached a convicted felon with charges pending and “offered to reduce charges that had been filed against him in return for his vote.” That person then voted illegally (it is illegal for felons to vote before completing their whole sentence, including probation or parole).

- Several other felons also voted illegally.

- Six apparently unrelated first-time voters listed the same single-wide trailer as their address when they voted, and a further nine people listed the same PO box as their mailing address.

While the proportion of absentee ballots cast for Neill was also unusually high, no evidence has emerged linking his campaign to election fraud.

Banks won the 2010 election, 52–48 percent. Banks defeated Neill again in 2014, 56–44 percent, with 9.2 percent of all ballots in that race cast by absentee ballot. In 2018, when Banks comfortably defeated an unaffiliated challenger, the proportion of absentee ballots went down to 5.5 percent.

Election officials gather evidence, and then … nothing

Election officials knew they had a problem in Yancey County.

Gary Bartlett, the executive director of the State Board of Elections (SBE) from 1993 to 2013, said that the agency had been investigating allegations of election fraud in Yancey County since “before election day.” As part of that investigation, two SBE employees, Jennifer Sparks and Karen Brinson (later SBE Executive Director Karen Brinson Bell), seized several hundred pounds of documents from the Yancey County Board of Elections (BOE). The documents included absentee ballots, the one-stop ballots, and absentee ballot request forms. Yancey County BOE Chairman Charles W. McCurry said, “They brought a Ford Taurus; the trunk was full [of seized documents], the back seat was full.”

And yet, neither election officials nor law enforcement took any action.

Marshall Tutor, an investigator for the SBE, told reporters in the wake of the 2018 Ninth District ballot-harvesting case that he found similar absentee ballot fraud in the 2010 Yancey County sheriff’s race but could not get the local district attorney to act:

It was rotten to the core on absentee ballot and vote buying, people getting drugs for votes, and that kind of thing. … That campaign was rife with absentee ballot fraud, and I couldn’t get the D.A. to do anything about it.

In the same article, Barlett said that the Yancey County case was one of “more than half a dozen” cases of alleged absentee ballot fraud referred to law enforcement during his tenure with no action taken:

We’ve reported it. We’ve had the (State Bureau of Investigation) turn us down. … There have been referrals (to local prosecutors) and nothing has been done.

But election officials did nothing, either.

The SBE has ordered new elections when there was evidence of fraud or mismanagement sufficient that the actual winner of the race could not be determined. They ordered a new election in the Ninth Congressional District after the 2018 election. They could have done the same for the 2010 Yancey County sheriff’s race.

Below are documents obtained through a public records request to the SBE. They are primarily emails and attached documents that provide further context and allegations.

Have we learned our lesson?

If law enforcement and election officials had taken action in Yancey County and the other “more than half a dozen” cases of suspected election fraud, it is possible that the fraud that forced a new election in the Ninth District would have never happened. Alas, it was not until that case that prosecutors and election officials took action to address absentee ballot fraud.

The General Assembly passed a rare bipartisan election bill in 2019 to make it more difficult to commit absentee ballot fraud. But that and other laws will protect our elections only if law enforcement and election officials enforce them.